The girl’s mother sent her to the store for meat but the girl, when she arrived, could not remember which cut was requested, or even which animal. She stood with a hand resting lightly on the cool glass of the case until the butcher – a bachelor handsome to some but repulsive to others – approached, wiping his hands of the blood that accompanied his trade.

What does the young lady require? he asked, looking at each part of her with his professional’s eye.

The girl was among those who found the butcher repulsive, so she turned to leave, suppressing the rise of a gag.

Perhaps, he called, if nothing here will suit, she would like to see something else – out back?

The girl’s curiosity often led her into troublesome situations, but she considered it part of the pact her soul had made in order to gain entrance to the world, and did not worry much over what befell her. Behind the butcher’s shop was a little dirt yard where a dog was tied, surrounded by many gnawed bones. Sitting on a stump of wood was a large iron skillet.

I made that, he said. Lift it, he said.

But the girl could not lift it, and she wrinkled her face in displeasure. What good is a skillet you can’t lift? she said.

The butcher frowned. He gripped the handle and swung it easily, carelessly. He thought of swinging it against the girl’s head but knew the timing was not right.

The girl walked to where the dog was tied and squatted beside it. What a pair you make, said the butcher. And indeed the picture gave him a great deal of pleasure. It rippled up and down his arms and legs, erecting the many dark hairs to be found there. To get a better look, he strode to where the girl was and gripped her by the back of the neck. He lifted her easily, carelessly.

The girl limped home carrying a packet of liver, but by the time she arrived, her mother was gone. It was just as well, she thought – her mother hated liver.

The girl waited many days, but her mother did not return.

She sat in a dry tub upstairs, eating crackers and thinking. Occasionally she stood to peer from the high, narrow window into the yard below, but the grass and other plants lay drab and useless as ever.

She concluded that her mother must finally have found the man she’d been seeking since the departure of the girl’s father on the eve of her birth. She knew her mother to be a kind woman, but one ultimately dominated by the demands of her sex, which – as she aged – became increasingly totalitarian.

*

News of the girl’s marriage to the butcher was received without surprise or comment by the people of the town. But after she’d been married a month, the girl – who really was still a girl – saw that what she’d endeavored to understand was not so complex. It wouldn’t do. She rose in the night to roam the woods that edged the town, and there learned many interesting things. The sky was cold and distant and hard, but no matter – she obscured it with her smoke.

Mornings before work, the butcher blackened iron and hammered it into shape on his hobbyist’s anvil. He blackened the girl, too, but she was less malleable than he’d hoped, so he kept her out back with the dog while he sawed bones and clasped hands in his immaculate shop, his white teeth testimony enough for any who might ask.

The dog was an old gray-faced bitch. She was too old to bear pups, but she cared for the girl as best she was able. When the girl was cold, she warmed her, and when the girl was hurt, she licked the wound until it healed. But when the girl died, there was nothing to be done – and the dog sank into a silent dream.

An abundance of flowers surrounded the girl at her funeral, an event well-attended by the people of the town. She did not look quite dead, which eased the proceedings.

To everyone’s astonishment, a handsome stranger was soon recognized – the girl’s father, returned at last. How had he come to be there on that particular day? How far had he traveled? Where had he been and what had he seen these many years? The father stood at the center of the crowd, shaking hands, his smile wide and benign.

The girl’s father spent what remained of the day with the butcher, who prepared a hearty meal of his choicest cuts. The two men took a quick liking to each other. As they ate, the father said, Tell me, butcher – what was she like?

The butcher – saddened suddenly by the absence of the girl – could think of nothing to say. She was always hungry, he pronounced at last, and she enjoyed eating whatever was placed in front of her.

When they finished, they stepped outside to admire the slow decline of the sun. They walked in a leisurely fashion, arriving finally at a little pond beloved for its middling beauty. Along its banks lay heaps of small, smooth stones which they kneeled on to paw through. Handled properly, a good stone would jig happily, prettily across the surface until exhausted. As the men understood it, the trick was to hold the thing lightly – tenderly – and then, with a swift jerk, send it spinning.

After they’d been at it a while with some success, they paused to observe a pair of figures a little farther down the shore.

Well would you look at that, said the father, shading his eyes for a better view.

It was the butcher’s old bitch – awake now, and mounted on the hindquarters of a young rascal about town, an impregnator par excellence. She gripped his neck with her teeth. Though he cried and struggled, she took her pleasure with the strength of one suddenly possessed by some fresh and vigorous spirit.

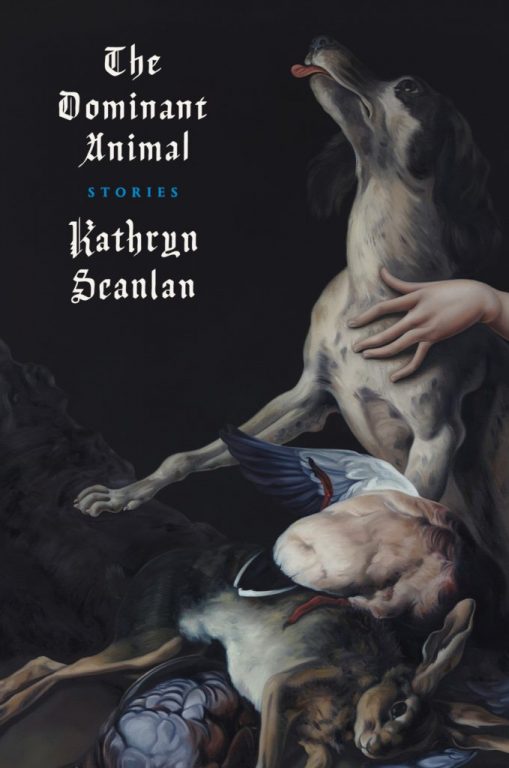

‘Fable’ is included in Kathryn Scanlan’s new collection, The Dominant Animal, published by Daunt Books.

Cover Image: detail from a painting by Gustave Caillebotte